While practical experience can be invaluable for the US educator, it is important for teachers and teacher leaders to utilize tools and techniques proven to be successful through research. In their article, “How Teachers Can Use Scientifically Based Research to Make Curricular and Instructional Decisions”, Paula and Keith Stanovich (2003) point out that teachers are just like research scientists. Consider the following scenario presented in their article: “…they (teachers) evaluate their students’ previous knowledge, develop hypotheses about the best methods for attaining lesson objectives, develop a teaching plan based on those hypotheses, observe the results, and base further instruction on the evidence collected.” This cycle very closely resembles the scientific method. Moreover, when laid out in this manner, it should seem very familiar to most classroom teachers. Therefore, if teachers and research scientists share a similar scientific process, it would seem a probable conclusion that both would rely on the latest research to guide their process. This however is often not the case in the classroom. With the pace and demand of a classroom, teachers find it hard to manage time in a way that allows for their own education. In a 2006 survey* including 21,000 teachers in the state of Kansas, 61% of the teachers didn’t think they had enough non-instructional time to do their jobs, let alone consider spending time researching best practices. 98% percent of teachers surveyed also said they spent time on school-related activities outside their regular workday. Thirty-seven percent of those said they spent more than 10 hours a week outside their regular workday. Given those statistics, one can easily see how our teachers struggle with time. It is also easier to understand why teachers struggle with keeping current on educational research. There is clearly very little time available for more than their own instructional process. So, how do we help our educators apply the latest research to their classroom instruction when time limits their ability to do more than teach? This question does not come with a package answer, but there are many ways to address the issue. Consider the following strategies: 1. Utilize school administration and staff leadership to source and present “relevant” educational research to the teaching staff. 2. Ensure a percentage of all staff professional development is dedicated to the study and discussion of the latest educational research. 3. Establish a Professional Learning Community (PLC) utilizing goals for learning established by the learning community. (Rotate PLC responsibilities so that the study and learning is done by rotating groups, and then shared out for discussion.) 4. Build connections in the greater educational community so that educational research can be presented by outside experts to the teaching staff as a service to the school. 5. Create a staff newsletter designed to highlight the latest research in education. 6. Create partnerships with local colleges or universities, offering up classrooms for potential educational research projects. 7. Encourage staff members pursuing a masters or doctoral degree to conduct their research at their own school site. While it may never be possible to create a system where educators have extra time to spare, it is important to ensure our educators still have access to current information revealed by the scientific research community. Likewise, it is also important to find ways for our true field-researchers in education (our teachers) to share their work and discoveries with those in the more traditional scientific realm. Tommy Reddicks Indianapolis, IN * 2006 Kansas Teacher Working Conditions Survey

0 Comments

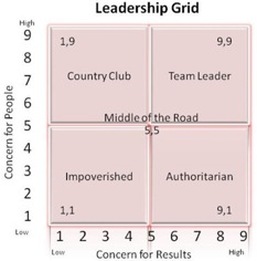

Leadership is a constant struggle between the use and influence of power and the need to develop respect. While many leaders have found success through a process of intimidation and rudeness, others have found success through fair and respectful oversight. Nevertheless, research is telling us that the fair approach is not necessarily the most successful. In the Harvard Business Review article, Why Fair Bosses Fall Behind, the title question is addressed. Lab studies and responses from hundreds of corporate decision makers and employees began with the age-old question, “Should leaders be loved or feared?”. Going a step further, the researchers in this study also asked, “Can you have respect and power?” The findings were clear. It’s hard to gain both. To solidify that point, the study also yielded another consistent piece of information expressed in a range of industries: “Decisions about high-level promotions most often center on perceptions of power, not of fairness”. According to the study, a very similar preference was demonstrated by students in a lab setting. Each witnessed a “manager” telling an employee about a compensation decision. Manager A communicated the decision rudely, Manager B with respect. The students were then assigned to work in a group led by the manager they’d observed; afterward they rated their leader’s power. Rude Manager A consistently scored higher than respectful Manager B—even though there was no difference in how they’d treated the participants themselves. By observing both the rude and respectful behavior, students had enough sensory influence to create a true bias. It is easy to argue that extremes on either side of power or fairness are faulty, but what does this research tell up-and-coming leaders who are working to solidify the push and pull of their leadership style? It suggests that a leadership approach devoid of power may struggle, especially when a stronger example of power already exists as a comparison for others in the workplace. It would also suggest that a very serious, direct approach when beginning a leadership position would be taken more seriously than an approach of fairness, kindness, and mutual respect. This discussion brings up the familiar question, “Is it better to be liked or respected?” Research is telling us that leaders who push hard for policy, process, and results in spite of relationships or kindness have a distinct advantage over those who choose the inverse path. Research is also telling us that “being liked” is secondary to success. Therefore, it is easy to understand the influence of a stronger, meaner leader. However, while these “superleaders” may demand more respect and higher achievement in the workplace, employee burnout can quickly become a side effect. C. K. Marshida’s article Employee Dissatisfaction Leads to Burnout, discusses this issue and suggests that employees are the backbone of the organization. She says that when the employees are fractured, the organization cannot stand strong. In Susan E. Jackson and Randall S. Schuler’s article Preventing Employee Burnout, some solutions for avoiding employee burnout are proposed. They say, In addition to increasing employees' feelings of control, participation in decision making may help prevent burnout by clarifying role expectations and giving employees an opportunity to reduce some of [their] role conflicts. Conclusion It is clear that stronger, more direct leaders will be perceived as more influential and more successful. However, strong leaders should leverage strategies for creating employee buy-in and employee empowerment. This will help to avoid employee burnout and sustain a stronger organization over time. It may be hard to act in a way that puts relationships and friendships in jeopardy, but if relationships and friendships are the backbone of your leadership style, you may find it harder to gain respect and authority. In considering the development of positive relationships and friendships in the workplace, it is better to understand them as a welcome side effect (when they happen) to a leadership style. It is important to keep the idea of fairness in terms of “what is fair for the organization” and not “for the individual”. While this can be perceived as calloused to individual employees, the consistency of a global vision helps remove bias or narcissism from the chain of command. Tommy Reddicks Indianapolis, IN |

Categories

All

AuthorTommy Reddicks has been a teacher and administrator in Wyoming, Arizona, Washington, Colorado, and Indiana since 1995. Archives

July 2016

|